Building a training academy for cancer-killing T cells

Written by: Janet Huisman, Øyvind Halaas and Otto Paans

“Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world.”

– Nelson Mandela

Have you ever wondered what you would do when your country was being attacked? Would you fire rockets and fight at the borders, or would you hide and hope that others would come to your aid? And what if the threat came from within? How would you eliminate that threat? For one thing, the internal enemy is harder to detect than the external enemy.

But if you had been to an academy where they taught you how to fight, how to recognize the internal and external enemy and how to communicate with your fellow soldiers – how would things look then? And, maybe if you would have been taught how to build a big and strong army, maybe then you would stand a much better chance. Education and training, after all, is the most powerful weapon.

To optimize this immunological education is exactly what we are attempting to achieve in the INCITE project. But instead of training humans, we are educating T cells. We aim to provide them with the capabilities and physical characteristics to fight effectively against tumours. Except, in our case, it is our body that is being attacked from within by a group of rebellious cancer cells. Our soldiers are anti-tumour T cells, who know a little bit of how to fight, but are not strong enough to eliminate the tumour completely. Moreover, the enemy has a few tricks up its sleeve: cancer cells can pass as the body’s own cells and avoid recognition. In that manner, the tumour can grow unnoticed, and is often only noticed once it starts to press on surrounding tissue or organs. Moreover, the tumour creates an environment around itself that is hostile to T cells and that inhibits their capacity to attack.

But if we could teach T cells how to fight more effectively, how they can recognise the cancer cells and how they can communicate with each other, they could form a big and effective army together.

In the INCITE project, we are building an artificial “immune niche”: think of it as a training academy for T cells where they acquire the characteristics that they need to fight effectively for prolonged periods of time: stamina, robustness and resilience. However, this is easier said than done. To realize such an academy, a lot of research is required, because nobody has ever attempted to build such an educational environment for T cells before. So, we need to accomplish a few steps before the academy is fully functional. We outline these below.

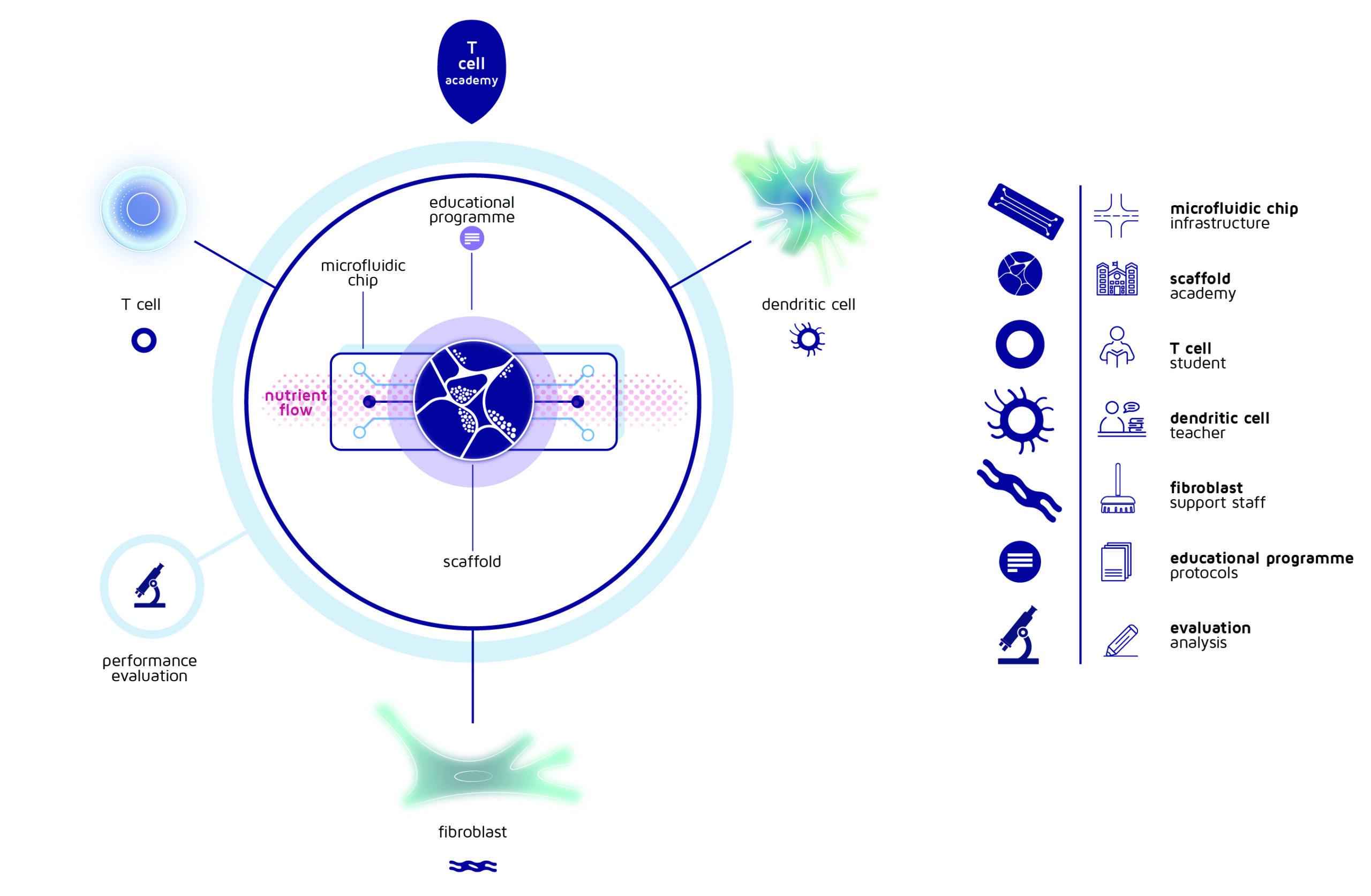

Figure 1: INCITE T cell academy concept

Academy: the microfluidic chip

First of all, we require a physical academy. But what should it look like? Should it be tall like a skyscraper or would a low-rise building be better? How big should it be? How many doors do we need? And which building materials should we use? In other words: what are the best dimensions for those inhabiting it? What is the rate of traffic (in this case: fluid flow) through the building? These questions are important as we need the various cells inhabiting the structure to thrive and multiply. So, we need to study the conditions in the human body to see what the academy’s inhabitants like best.

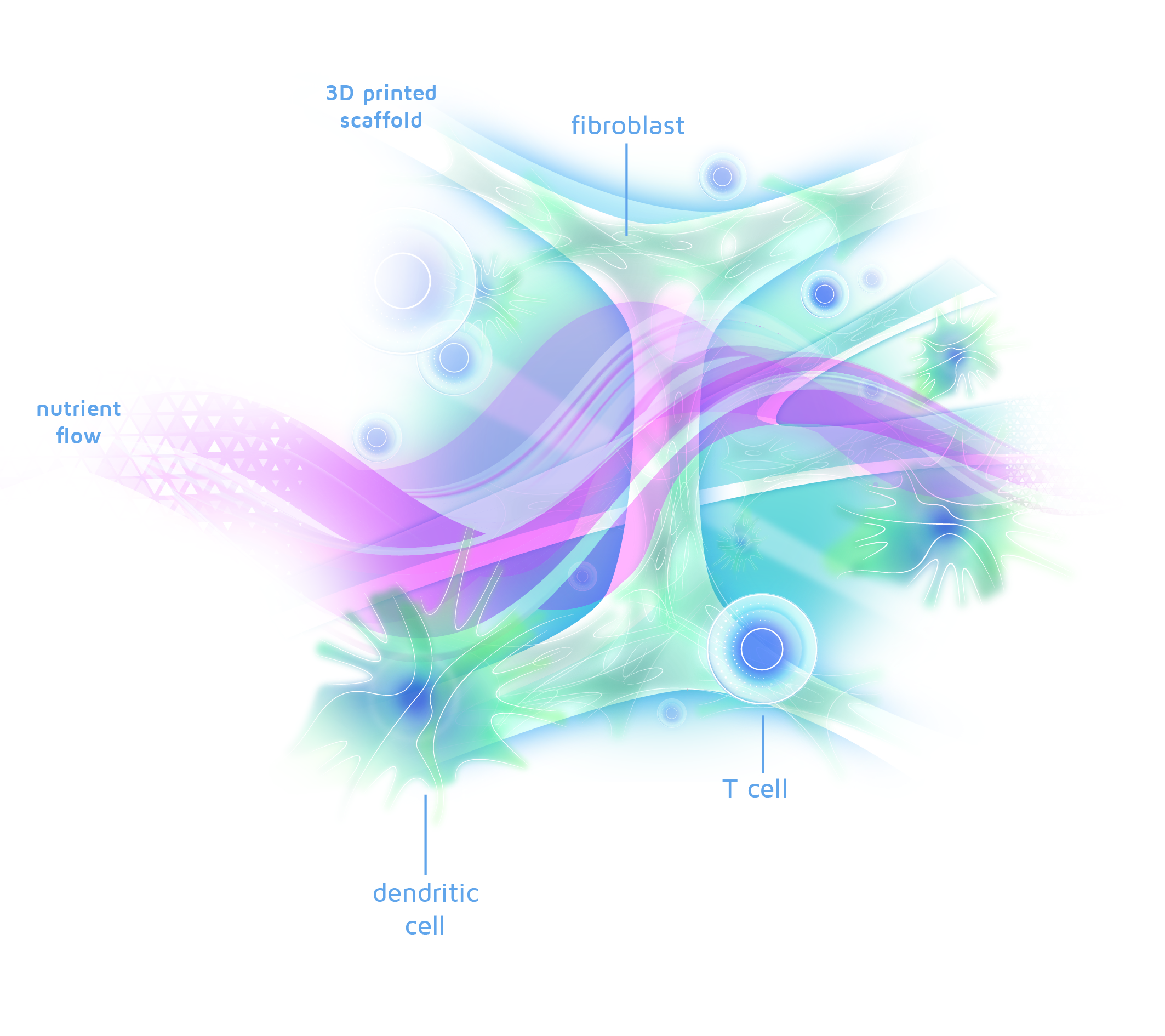

Interior: the scaffold

Next, we need to think about the layout and the interior. Do we want a lot of small classrooms or do we also need some big ones? How do we make sure there won’t be any congestions in the hallways? And how many seats do we need? These questions seem a bit counterintuitive, but the cells require space and nutrition. The nutrition is “pumped” through the scaffold. However, it must pass by all the cells, so they stay alive. But on the other hand, the interior cannot be an open plan, as the cells also need some handholds to cling to.

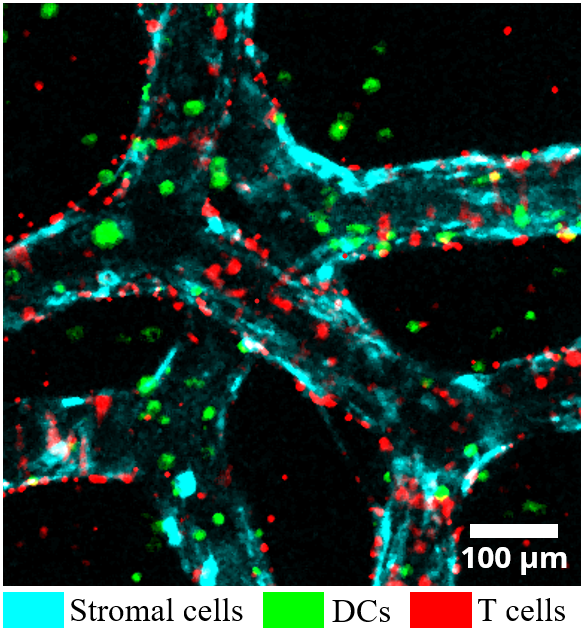

Figure 2: Image of the interior of the scaffold. The different types of cells have been coloured for easy readability.

Teachers: the dendritic cells

Once the academy is finally built, we need to start hiring teachers. But which teachers are the best? How many do we need? And will they need additional training before they can start teaching the T cells?

Supporting personnel: the fibroblasts

Probably we will also need some supporting personnel. Think of them as the staff, such as cleaners and people who provide lunch in the canteen. How many will we need of those, and who are best suited for the job? Do they also need additional training, and if so, how do we give it to them? In the immune niche, a type of cells called fibroblasts (also called stromal cells) perform the supporting tasks, and so we populate the scaffold with them. They help creating an environment in which dendritic cells, T cells and fibroblasts can thrive.

Students: the T cells

Now that everything is prepared, we can finally admit some students aspiring to become soldiers to the academy. But how many places are available? And can we somehow preselect those with the high chance of success? Our body does not produce enough soldiers to overcome a solid tumour, so we need to invite students from outside the body as well – think of them as clones of the cells that reside in our body. In the future, we’d like to select the T cells with a high potential to become effective T effector (Teff) cells. These are the “killer cells” that our immune systems send in to fight the tumour.

Figure 3: Illustration of the interior of the scaffold, with the 3D-printed structure, the different cell types and the nutrient flow

Education programme: the protocols

Instead of just putting the students together with a teacher in a classroom, we probably also need to develop an education program to guide them. Because what courses will we teach them exactly? Should each student get classes from several teachers, or is one teacher enough to teach them everything they need to know? And how long should the students even stay in the academy? Are a few hours enough, a few days, or a few years? In INCITE, we aim for a very specific programme: T cells are taught to recognize tumour cells. Each tumour cell has an “antigen”. Think of it as a mark that singles it out as “the enemy”. In the academy’s educational programme, T cells are taught to recognize this mark, and to attack when they see it.

Quality control and education: output analysis

After the soldiers have finished their education, we would like to make sure they are fully prepared for the field. Of course, we could just send them to the battlefield and see what happens. But maybe we can also check earlier already if they have the characteristics of a good soldier, for example with a final test. But what defines a good soldier? Should they be very strong, or have great stamina? Or should they be good at communicating with other soldiers to recruit many more new soldiers? And what is “good”? Can we measure that in a certain way?

As you can see, there are many challenges to overcome when building a “military academy” for T cells. That is why INCITE is working with over 20 people from 6 different European countries for 4 years to realize this. And although it is not always easy, we try very hard to make our T cell academy a little better every day. Because we really believe that with this academy, we will be able to make a big step towards a better treatment of solid tumours. Importantly, our method does not need chemotherapy, but uses the intelligence already present in nature. We combine it with the latest advances in technology in a feat of micro-engineering. And perhaps, one day, we can treat people for cancer while maintaining their quality of life!